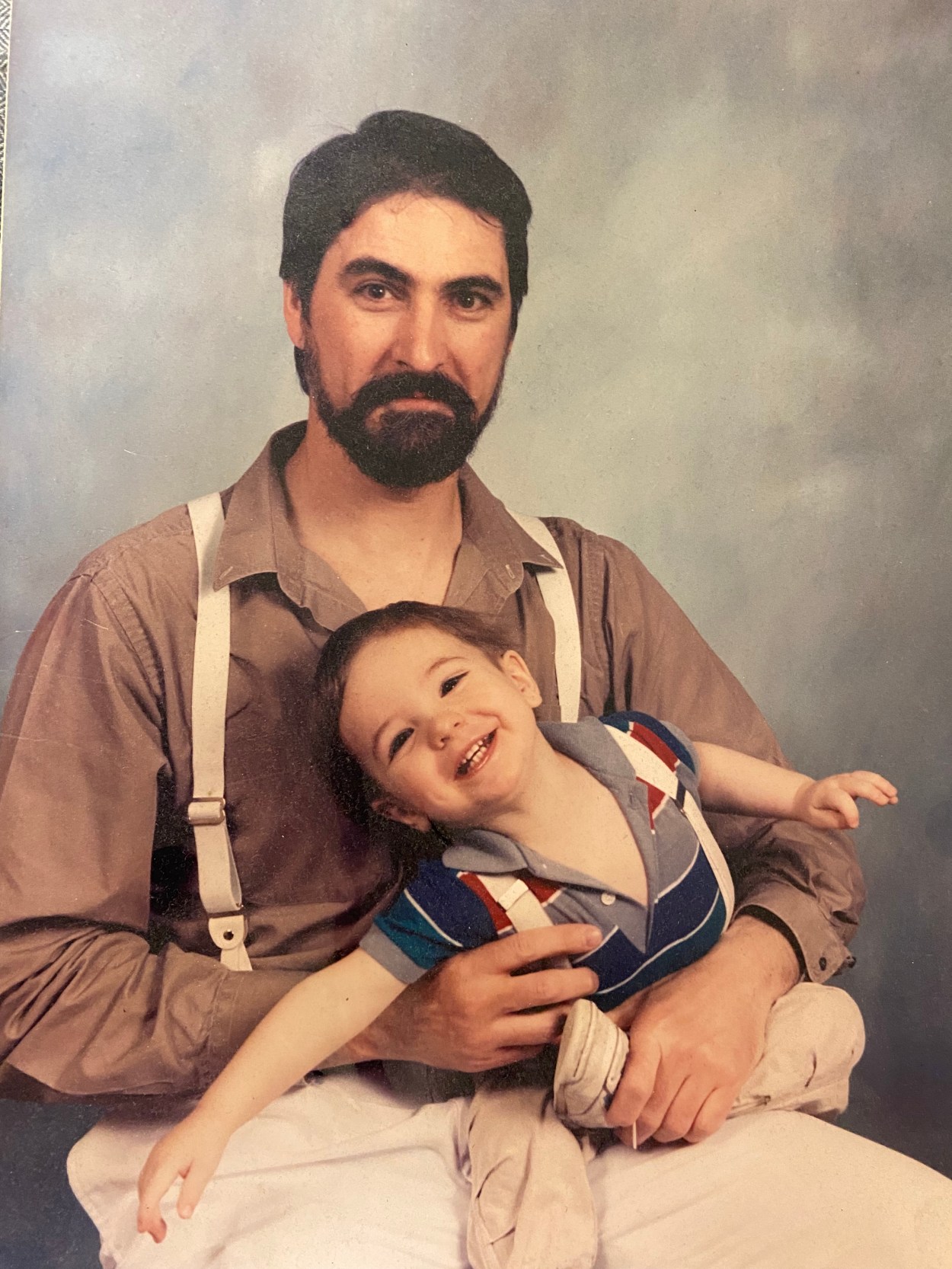

I see before me now a glimpse of my life in the late 1980s. I see myself as I was then: dark-eyed with a full head of brown hair; grinning like a goober; my whole body splayed out to encompass my already massive personality; clad in suspenders, a striped polo shirt, khakis, and sneakers, and cradled in the strong arms of a man who loves me. That man is himself in suspenders and khakis, wearing a long-sleeve taupe shirt. He is handsome and wiry, with jet-black hair and beard, green eyes and a nose that would rival a Roman emperor’s, his face painted with the pained but gleeful rictus of someone who must manage a toddler on a daily basis.

Due to my balding head and fifty pounds of excess weight, I find it often difficult to see the resemblance between myself and the thirty-nine-year-old in this photo, but everyone who sees it swears up and down that I look exactly like my father. If I was skinnier and put on a hat, perhaps, but it is more than obvious to anyone who knows the both of us that the bulk of my personality is a mirror of his; despite some inheritance of my mother’s traits, I take enormously after him. And yet it is a paradoxical but all-too-common fact of the human universe that similarity breeds contempt. That mirror can be a window into everything we find horrible and ridiculous; and two fires, burning with equality, which join together will create an inferno that destroys all it touches. Thus, despite the love between us as shown in the picture mentioned above, a love which from his end never wavered in its own sort of authenticity and ardor, the reality of our likeness is frequently sobering and even dreadful.

He was a volatile narcissist who was repeatedly cruel to his wife and children and obnoxious to his peers, acquaintances, and clients. Aside from a few “drinking buddies,” he had almost no friends by the time of the illness that rendered him helpless and senile (he is at the present still living, peaceful and relatively content). He was childish and fragile, prone to tantrums and regular outbursts of outlandish and cutting verbal abuse when he wouldn’t get his way, as if he had never been introduced to a sense of proportion and standards of courtesy. He regularly had an open relationship with reality and gave himself airs of infallibility that would embarrass a pope. Thus, every point of contention, no matter how insignificant, was a hill he would die on and die screaming, taking the other with him. Tension was the constant rule in our household, with regular bouts of trauma and terror. The germs of these horrors (and, indeed, the occasional blossom) I can often find in myself. It would not be inordinate of me to say that I feel blessed and grateful that I am not called to bring up a family lest I transmit unto another generation the woe in which I was raised.

And yet for all the years of such vicious conduct, I cannot be too stern with him looking back on his parenting. He was a deeply wounded man with oozing sores on his soul that were never salved nor bound. He was brought up in great poverty, he never knew his biological father, and immediately after high school he did a tour in Vietnam for three years. I know relatively little of his life before I entered the picture, but the aforementioned facts (combined with a few other painful experiences of his which I will not mention) inform me enough of the misery of the three quarters of a century he has spent on earth. He was not a monster; he was a tortured soul. He was not evil; he was tragic.

He was also not without his own talents and graces. He was a highly intelligent and even sophisticated man, he had a proficient grasp of wit and irony, he was a hard worker, he was a skilled architect, and a maestro in the kitchen. He passed on to me everything from a love of cooking to a love of science fiction, and nearly every element within myself that could be described as “academic” or which aspires to a cherished appreciation of “higher culture” I get from him. But more than all of these (and not to excuse or gloss over what was previously stated) he had undeniably good qualities as a father. I return to the photo mentioned above: this image is no pantomime, no charade to mask some horrible and immutable darkness void of familial love. The man loved me and loves me still; he never failed to say so. Despite his barbarity, he was also a tender and affectionate parent, even doting. He was warm and never stingy about dispensing hugs and kisses. Though withering in his criticism, he was also lavish with praise, and he never ceased to be proud of me. He was solicitous and generous to the point of being foolhardy, but this is an excess of a virtue, not an absence of it.

In childhood, he was my hero; my regard for him was quasi-idolatrous. For much of my adolescence and twenties, he was my Antichrist; I have never in my whole life despised someone so much as I have him. These days, while I by no means idolize him, I have no more hatred for him, either. Admittedly, certain flashes of memory can give me moments of acrimony, but these pass quickly enough and I find that I have some fondness for the old man. And now with his senility and his most definitely being in the twilight of his years, I miss the interactions we would have. I miss his wit and sense of humor, I miss the conversations of high intellectual value that were sometimes ours, I miss watching TV and movies with him. I even miss getting drinks with him, despite the poor fool not being able to hold his liquor as well as his son and his being a rather tedious drunkard past a certain point. As was aforementioned, I take enormously after him, and when he makes his exit from society, there will be no one on earth quite like me as he is. Though some of my resemblance to him worries or embarrasses me, I’ve also learned to correct the vices of his heredity, to emphasize his virtues, as well as to express qualities I receive from other influences. Thus, I mimic his pomposity but also check it with self-deprecation; I am resolute in my beliefs without being dogmatic; I can be funny and charming without sucking all the oxygen out of a room; I revel in my nerdy obsessions and eccentricity without alienating people. From him, I get an equal thirst for refinement and vulgarity, a thrill to show off and entertain, and a yearning to smother those dear to me with syrupy affection – all a decent starting place for my character.

For nearly two decades, my similitude to the old man made me shudder and quest to purge myself of all traits passed down to me from him. A futile endeavor, as I cannot help being who I am, and who I am is very much a facsimile of my pater. But futile also because it springs from a misunderstanding of what it means to inherit from one’s parents, as such inheritance is something to neither reject nor cling to. They are merely the base elements from which we construct our own identity through the action of our will and the environs of our own experience. If I’m placed in a run-of-the-mill kitchen and enjoined to make a meal with whatever is in the cupboards and refrigerator, I am of course limited by what’s available, but what I create will be the result of my own choice and creativity. What someone else will make, placed in the same situation, will be entirely different. And though I may wish to make pasta for the starch when there is none to be had, fried potatoes are nonetheless suitable; rather than lament the absence of ginger, I can accept cinnamon as a fine substitute. But this culinary analogy is insufficient – in real life, we bring outside ingredients for the recipe of our personalities beyond what our family provides: from teachers, peers, religion, society, books, movies, music, careers, etc. Our kitchen is the world entire.

I will always be radically like the man who sired and raised me. But the basics I get from him are not all bad, some of which I express with enthusiasm. That which I suppress I can replace with other influences. Indeed, I can manifest other facets of my character from my own free creativity. But the foundation of myself was crafted, one way or the other, by a particular architect. This I cannot escape, nor do I need to. In many ways, I have risen above his mistakes and I also cherish his gifts. I must also face the fact that he has seen more sunsets than he’ll see, and so I hope that when “passing from Nature into Eternity” he may, through God’s mercy, obtain a final and everlasting pardon, joining the citizens of heaven. From there and through his intercession, he may do more perfectly above than what he did for me on earth below: love me, look out for me, assist me, and guide me to fulfillment of myself in this life and into the bliss of the next.

Michael,

A beautiful tribute to your relationship and kinship with your father. As with most all of your written works, you are ever present.

LikeLike

Thanks, sweetie! 😘

LikeLike